Introduction to Warli Art: An Ancient Indian Tradition

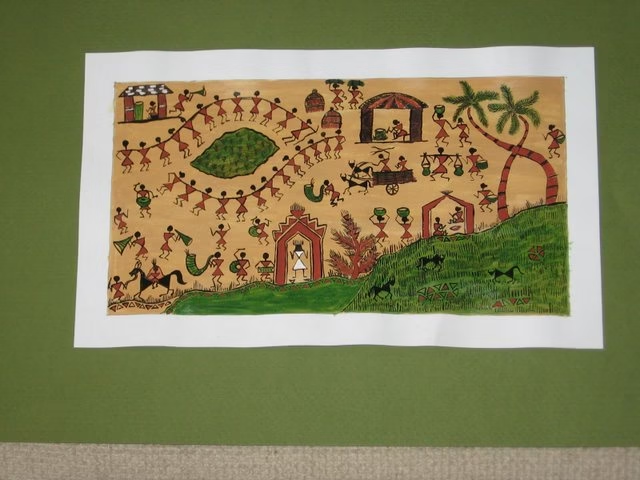

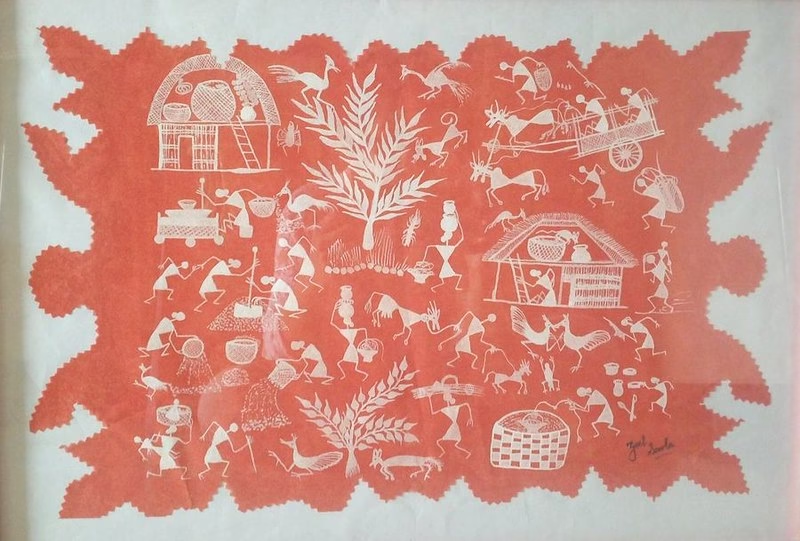

Pictures of Warli art, an ancient tribal tradition from Maharashtra, speaks the language of simplicity. The Warli tribe, known for its profound connection with nature, has preserved this art form for centuries, passing it down through generations. The medium is unpretentious: white pigment, made from rice paste, is applied on mud walls, creating stark, powerful imagery. The shapes are simple, geometric—circles, triangles, squares. Yet within this simplicity lies an intricate story, a world that is at once timeless and utterly contemporary.

The motifs—humans, animals, trees, and symbols—speak of an intimate relationship with the earth. The human figures, drawn with a sense of motion, appear almost suspended in time. The animal figures, some fantastical, others eerily familiar, are woven into the fabric of daily life. Trees are often depicted, their branches reaching out like hands, weaving a connection between the sky and the earth. These are not mere decorations; they are the tribe’s life, its spirituality, its story.

Pictures of Warli art is rooted in ritual. It has been used in weddings, festivals, and rites of passage. Its power lies not in its aesthetic appeal but in its rawness, in its reflection of a world untouched by the hustle of modernity. The first documented Warli paintings date back to the 10th century. Today, this art form speaks to a global audience, its authenticity preserved in the very act of painting.

The Origins of Warli Art: Tracing the Roots

The origins of pictures of Warli art are traced to the Warli tribe of Maharashtra, a people whose existence is entwined with the earth itself. This art, believed to be at least 2,500 years old, is rooted in the deep forests and rural lands of the Western Ghats. The Warli paintings, initially found on the mud walls of tribal homes, are crafted with a simple technique: rice paste mixed with water, applied to an earthen backdrop.

The art form is a visual language—one that does not conform to the complex illusions of urban life. It speaks in circles, triangles, and squares—primitive yet profound symbols. Circles, for instance, are not just shapes; they evoke the eternal movement of the sun and moon. Triangles are sacred, representing the sacred mountains. Squares denote human settlements, grounded in the village’s intimate connection to the earth.

In its early years, pictures of Warli art was kept hidden within the confines of the tribe, never seeking the gaze of outsiders. Yet, by the late 20th century, as the world began to fracture the sacred with the profane, the art form emerged into the public sphere. It wasn’t until 1970, when Jivya Soma Mashe, a Warli artist, was encouraged to share his work, that the “pictures of Warli art” gained international recognition.

What was once confined to a home’s wall, now graces the walls of galleries, museums, and contemporary spaces. Yet, despite its ascent into the world of fine art, the essence remains unchanged— a narrative of survival, of nature, of life’s sacred rhythms.

The Symbolism in Pictures of Warli Art: What the Pictures Represent

The symbolism in pictures of Warli art speaks in the language of nature—raw, unpolished, and intertwined with the rhythms of the earth. It is an art that lives, breathes, and continues to evolve, yet its essence remains rooted in the deep, sacred relationship between the Warli tribe and their environment. Each symbol, every stroke, carries meaning far beyond aesthetics.

The circle, for instance, is more than a shape; it is the sun, the moon, and the earth. The Warli people, who have lived in the forests of Maharashtra for centuries, view the circle as a symbol of the eternal, cyclical nature of life. It signifies the passage of time, the birth, death, and rebirth that characterize the human existence. In a world driven by seasons and the unyielding force of nature, the circle is a reminder that everything returns, everything recycles.

The triangle, another core motif, is steeped in meaning. It represents mountains and trees—the lifeblood of the Warli tribe. The tribe’s relationship with nature is not one of domination but reverence. The triangle is a tribute to the towering mountains that stand as silent witnesses to the tribe’s struggles and survival. It is the sacredness of the forest, a place both bountiful and unforgiving, offering sustenance and shelter to those who understand its language.

The square, seen in many pictures of Warli art, is a sanctuary. It is not merely a geometric figure but the representation of the sacred enclosure, the ‘ritual space’ where life unfolds in all its human simplicity and complexity. The square is where rituals occur, where the community gathers to celebrate, mourn, and mark the passage of seasons.

Animals, too, find their place in this sacred geometry. In pictures of Warli art, the deer, elephants, and tigers are not just creatures of the wild; they are symbols of the tribe’s connection to the animal kingdom, an acknowledgment of the delicate balance that exists between humans and beasts. These creatures, often depicted in motion, appear not as separate entities but as equal participants in the great cycle of life.

And then, there is the human figure, humble in its simplicity. It is not meant to dominate the scene but to be a part of it, dancing, hunting, farming, living. The humans in pictures of Warli art are often shown engaged in rituals or dances, signifying the tribe’s profound connection to the earth and the cosmos. These images speak not only of survival but of an existence in rhythm with the world around them.

Warli art does not speak in loud, clashing colors. It speaks in the quiet whisper of white pigment against the backdrop of the earth. It tells stories of survival, of harmony, of sacredness. It is not simply decoration; it is a language. A language that transcends time and place. A language that, in the simplest of symbols, tells the deepest truths of life.

The Techniques Behind Warli Art: Crafting Pictures with Precision

The method is deceptively simple. The Warli artists, hailing from Maharashtra, employ rice paste and natural pigments, often derived from the earth itself—white being the most prominent. White rice paste is applied directly to the canvas—a mud wall, a piece of cloth, or, in modern times, paper—using bamboo sticks or twigs. These tools, rudimentary and humble, bring forth shapes that are both primal and profound.

At its core, pictures of Warli art relies on geometric forms: the circle, the triangle, and the square. The circle, so simple yet so profound, represents the sun and moon, the cycle of life. It is the very essence of life, a symbol of unity and eternity. The triangle, pointing upwards, signifies the mountains and trees, embodying the natural world’s steadfastness. The square, placed with exacting balance, often depicts the human form, the essence of human connection to nature.

Pictures of Warli art is built around stories—stories of the hunt, of marriage, of nature’s eternal cycles. The animals are depicted with a few strategic lines, the body of a deer, the shape of a bird—all reduced to their essence. The visual language of Warli art is designed to evoke a sense of harmony, where every creature, every element, plays its role. It’s a direct representation of the human experience: simplicity, survival, and the spiritual.

Pictures of Warli Art in Modern Times: How the Pictures Are Evolving

As the modern world encroached upon the Warli tribal territories, there was an undeniable change. In the last few decades, pictures of Warli art has expanded its scope, with contemporary artists incorporating new themes and materials. This shift is not just an aesthetic decision, but a necessity for survival in a globalized art market. The Warli community, traditionally isolated and reliant on their art as a form of storytelling and ceremonial expression, began to realize that if their culture were to survive in the modern age, they would need to adapt.

The most striking evolution is seen in the medium of pictures of Warli art. From walls of homes to canvas, and more recently to digital formats, the pictures of Warli art now proliferate across exhibitions and online marketplaces. In 2020, the Indian art market saw a significant rise in the demand for tribal and folk art, with Warli leading the charge. According to a report by ArtTactic, Warli art prices surged by 30% in major Indian art auctions in the past five years, reflecting growing interest from collectors and the global market. This is in stark contrast to the past, when Warli art was largely confined to tribal communities.

Moreover, the thematic evolution is just as striking. Traditional Warli motifs, which once captured rural life, now grapple with contemporary issues. Artists depict urban landscapes, environmental destruction, and the challenges faced by indigenous people in a modernising world. They employ bold colours, intricate designs, and even experiment with mediums like digital art, which is gaining traction on social media platforms.

A study by the International Journal of Art & Design highlighted a 40% increase in digital reproductions of Warli art on global platforms like Instagram and Etsy in 2022. This allows artists to reach a wider, younger audience, many of whom see Warli art as a symbol of both tradition and rebellion.

The shift towards modern pictures of Warli art is not just artistic but socio-political. Artists are increasingly using their canvases to address contemporary issues like deforestation, gender inequality, and the displacement of tribal communities.

Warli paintings have been used as a form of resistance, with visuals that tell the story of people fighting for their land, identity, and culture. These pieces are a stark reminder of the fact that, while Warli art has evolved, its core message of living in harmony with nature, and the fight to preserve that balance, remains unchanged.

The Cultural Importance of Warli Art: More than Just Pictures

Pictures of Warli art, painstakingly etched on mud walls using bamboo sticks and rice paste, stand as a testament to the Warli tribe’s history, spirituality, and the constant struggle for survival against the encroaching forces of urbanization.

The Warli tribe, living in the forested regions of Maharashtra and Gujarat, have no written language. Their paintings, made with geometric precision, serve as their storybook, their history book, and their calendar. They depict daily life, agricultural rituals, and the sacred. These pictures are not just decorative; they are deeply spiritual, capturing the unseen forces of nature that govern life.

The circle, in Warli art, is sacred – symbolizing the cosmos, the cycle of life, and the interconnectivity of all living beings. The spiral, another recurring motif, reflects the tribe’s belief in the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth. It is said that the Warli people believe that everything is connected in a divine, cyclical web – their livelihood, their art, and their environment.

Over 30,000 years old, pictures of Warli art is one of the oldest surviving traditions in India. Yet, despite its ancient roots, it has remained tied to the daily lives of the Warli people, grounded in their agricultural rhythms and the natural world around them. The art survives in the face of modernization, when its practitioners are increasingly marginalized and their forests are razed for urban expansion. The connection between pictures of Warli art and nature is irreplaceable, and the survival of both is increasingly threatened. The traditional practice, once passed down orally within the community, has faced commercial appropriation in the form of mass-produced Warli-inspired textiles, leaving some artists in conflict with the global art market.

The recognition of Warli art as a Geographical Indication (GI) product, granted by the Indian government, has provided some legal protection. However, this has not shielded it from the tides of commercialization. Warli paintings, once confined to the mud walls of tribal huts, now adorn tourist souvenirs, fabric, and canvas. It is a double-edged sword: while the global market has provided economic opportunities for Warli artists, it has also commodified their sacred art. Some artists, like Jivya Soma Mashe, have carried the tradition forward, blending modern techniques with age-old motifs, while others are disillusioned by the idea of their culture being diluted for commercial purposes.

The irony lies in the fact that pictures of Warli art – once a tool of survival, depicting agricultural cycles, harvest rituals, and animal life – is now a symbol of survival in a different sense. It is the tribal artist’s struggle for recognition, a fight for the space they deserve in the rapidly evolving world of contemporary art. Yet, for all its commodification, pictures of Warli art remains a powerful means of resistance, an affirmation of the tribe’s enduring link to their land, their history, and their spirit. It is not merely about the pictures of Warli art that are produced today, but about what those images carry forward: a deep-rooted connection to a disappearing world.

For further reading on significance of block printing, you can visit these useful resources:

Check out our Blog Page on Traditional Indian art.

Leave a Reply